![]()

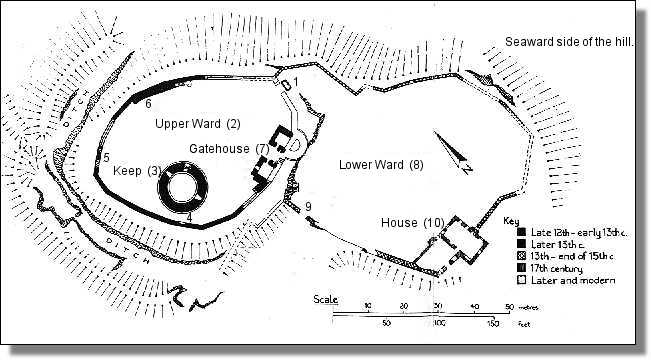

1: The original entrance, now just a gap in the ruined wall. The gate was formerly protected by a drawbridge

over a pit hewn from the rock on which the castle stands.

2: The Upper Ward, an area of about 2.5 acres, surrounded by a curtain wall built in short straight lengths.

The wall, which is just inder 4 feet thick, is generally well preserved, especially to the west, where it stands

to its full height, including the parapet. A wall-walk behind the parapet seems to have been just 18 inches wide, but holes through

the wall at this height would have held substantial timbers for a fighting platform.

3: The circular keep, built soon after the curtain wall, was once linked to it by a bridge from a door at the first

level. The main entrance was originally by another first floor door, on the south-east, now high above ground level, but formerly

reached by an external stair.

4: Near the keep is a pair of latrines, and the mark of a gabled roof over them is clear. The latrines emptied through

chutes, visible in the outer face of the curtain wall. 5: Three splayed loops, pierced through the outer curtain wall, perhaps made in the 15th century. Here, opposite the

original entrance, was a postern gate, the castle's "back door", but this was later bricked up, and is now only traceable from the outside.

6: This is a puzzling skin of masonry built against the north-eastern section of the curtain wall. Excavation nearby

found no trace of a stone building here, nor does the outer wall require strengthening at this point.

7: The gatehouse, added in the later 13th century, perhaps around the 1260s. Though now badly ruined, it must once have

been very strong and imposing. It was built onto the original curtain wall, with a central passageway between between two towers which

were square to the upper ward, with the more easterly of the two semicircular on the outside, and now alarmingly perched over an undercut

rocky escarpment.

8: The lower ward, now just a grassy expanse on the slope below the ruins of the castle, and once again its buildings can

only be imagined; probably a mixture of residential and agricultural structures. The lower ward wall, now badly ruined, is clearly later

than that of the upper ward (2), but there are no clearly dateable features, and its true age remains uncertain. One possibility is that

it was built in the 13th century, but it could well be later, when the castle was in Irish hands.

9: The entrance to the lower ward is by a simple pointed arch, with a draw-bar socket in the jamb. Near the south-west, where

the wall is best preserved, several splayed loops are visible, covering the easy approach from the north.

10: The house was built partly against and partly over the curtain wall, and was probably constructed in the early 17th century.

Now just a gaunt ruin, it must once have been a grand and very gracious dwelling house. The house is L-shaped, with the west wing probably

slightly earlier than the east. The rooms were on two floors, with a low basement under the east wing. All were provided with fireplaces and

were well lighted, with plenty of windows, some now blocked and some enlarged to form doors. The south gable of the east wing still stands

to its full height, and the scars of decorative triangular pediments can be seen above the ground and first floor windows. The west curtain

wall against which the house was built has two loops for defence, but the house itself appears to have been purely residential, with no

defensive features of its own. Dundrum Castle, does, therefore, illustrate the change that came about in Ireland in the late 16th and

early 17th centuries -- the transition from fortification to architecture.

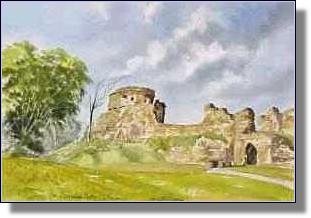

![]() This 12th-century castle with its circular four-storey high keep

was built by the Anglo-Norman knight John deCourcy on the summit and slopes of a 200-foot-high hill,

and was the object of frequent struggles between the invaders and

the native Irish.The castle was besieged and taken over in 1210 by king John,

and it remained in royal possession until 1227, when Henry III made it over

to Hugh deLacy the Younger.

This 12th-century castle with its circular four-storey high keep

was built by the Anglo-Norman knight John deCourcy on the summit and slopes of a 200-foot-high hill,

and was the object of frequent struggles between the invaders and

the native Irish.The castle was besieged and taken over in 1210 by king John,

and it remained in royal possession until 1227, when Henry III made it over

to Hugh deLacy the Younger.

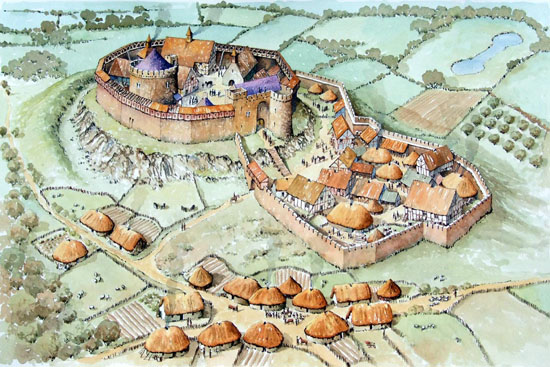

![]() The castle occupies a magnificent location, dominating the surrounding countryside and the sea.

It's a beautiful location to visit whenever you get the chance to come to Ireland, and one you won't soon forget. It is built on a prominent

hill of shale and grit, carved out by the ice during the last Ice Age. Bare rock is clearly visible, especially under the

gatehouse and in the defensive ditch which surrounds the castle. Situated on the western shore of Dundrum Inner Bay, it

commands a fine natural harbour which offered easy penetration inland, especially to the fertile Lecayle peninsula. This

strategic importance, recognised by the builders of the early Christian "dún" or fort, which previously occupied the site,

and those of the Anglo-Norman castle, was described by Lord Leonard Grey, who took Dundrum in 1538 as: "one of the strongest

holds in all of Ireland, and most commodious for defence of the whole countrie of Lecayle both by sea and land, for Lecayle

is environed by the sea, and there is no way to enter it by land but by the said castle". Although one of the delights of

the hill is now its tree cover, the surroundings of the castle must have been far more open at the time it was in use,

since trees would have provided unwelcome cover for assailants.

The castle occupies a magnificent location, dominating the surrounding countryside and the sea.

It's a beautiful location to visit whenever you get the chance to come to Ireland, and one you won't soon forget. It is built on a prominent

hill of shale and grit, carved out by the ice during the last Ice Age. Bare rock is clearly visible, especially under the

gatehouse and in the defensive ditch which surrounds the castle. Situated on the western shore of Dundrum Inner Bay, it

commands a fine natural harbour which offered easy penetration inland, especially to the fertile Lecayle peninsula. This

strategic importance, recognised by the builders of the early Christian "dún" or fort, which previously occupied the site,

and those of the Anglo-Norman castle, was described by Lord Leonard Grey, who took Dundrum in 1538 as: "one of the strongest

holds in all of Ireland, and most commodious for defence of the whole countrie of Lecayle both by sea and land, for Lecayle

is environed by the sea, and there is no way to enter it by land but by the said castle". Although one of the delights of

the hill is now its tree cover, the surroundings of the castle must have been far more open at the time it was in use,

since trees would have provided unwelcome cover for assailants.

Plan of Dundrum, also known as the Magennis Castle.

![]()

![]() After a hundred years the Magennises got hold of the castle,

but it was recaptured by Henry VIII's lord deputy, Garret Óg, Earl of Kildare,

in 1517, and again in 1539 by lord deputy Grey.

Fortified by Shane O'Neill in 1566, it once again reverted to the Magennises,

who held it until it was re-taken for the English by Lord Mountjoy in 1601.

Sir Francis Blundell bought the castle and estate in 1636, and lost it

temporarily again to the Magennises during the Rising of 1641. It was retrieved

by Sir James Montgomery, and afterwards garrisoned by Cromwellian troops, who

finally dismantled it in 1652.

After a hundred years the Magennises got hold of the castle,

but it was recaptured by Henry VIII's lord deputy, Garret Óg, Earl of Kildare,

in 1517, and again in 1539 by lord deputy Grey.

Fortified by Shane O'Neill in 1566, it once again reverted to the Magennises,

who held it until it was re-taken for the English by Lord Mountjoy in 1601.

Sir Francis Blundell bought the castle and estate in 1636, and lost it

temporarily again to the Magennises during the Rising of 1641. It was retrieved

by Sir James Montgomery, and afterwards garrisoned by Cromwellian troops, who

finally dismantled it in 1652.![]() It is said that this castle probably followed

the lines of the ancient pallisaded fort called "Dún Rúdhraidhe" (Rory's Fort),

which occupied the site in very early times. The ancient manuscript called

"Leabhar na h-Uídhre" (The Book of the Dun Cow -- to be seen at the Royal Irish

Academy in Dublin), tells of a feast given in Dún Rúdhraidhe by Bricriú of the

Venomous Tongue, in honor of king Conor Mac Nessa and the Red Branch Knights.

It is said that this castle probably followed

the lines of the ancient pallisaded fort called "Dún Rúdhraidhe" (Rory's Fort),

which occupied the site in very early times. The ancient manuscript called

"Leabhar na h-Uídhre" (The Book of the Dun Cow -- to be seen at the Royal Irish

Academy in Dublin), tells of a feast given in Dún Rúdhraidhe by Bricriú of the

Venomous Tongue, in honor of king Conor Mac Nessa and the Red Branch Knights.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Copyright © 2003 www.TaraMagic.com Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Liability, trademark, document use and software copyright rules apply.