Near the small town of Ballyboughal, in north County Dublin, is a narrow, winding roadway named Drishogue Lane, and it was here on July 14th,

1798, that the survivors of the rebel column which had set out from Wexford some weeks before made their final act of defiance against British

rule.

Though not participated in by any of the people of the district, the last battle of the opposing forces

of the 1798 Rebellion took place in Fingall, and local tradition is able to supply particulars with regard

to this engagement which amplify the somewhat meagre historical account.

As readers of Irish history will be aware, the Wexford insurgents' forces, defeated at Vinegar Hill and Arklow,

finding that their native county was being inundated with British troops, determined to evacuate it for

the time being.

Near the small town of Ballyboughal, in north County Dublin, is a narrow, winding roadway named Drishogue Lane, and it was here on July 14th,

1798, that the survivors of the rebel column which had set out from Wexford some weeks before made their final act of defiance against British

rule.

Though not participated in by any of the people of the district, the last battle of the opposing forces

of the 1798 Rebellion took place in Fingall, and local tradition is able to supply particulars with regard

to this engagement which amplify the somewhat meagre historical account.

As readers of Irish history will be aware, the Wexford insurgents' forces, defeated at Vinegar Hill and Arklow,

finding that their native county was being inundated with British troops, determined to evacuate it for

the time being.

They marched northwards as far as the village of Nobber, in county Meath, in the hope that they might arouse

Meath, Louth and counties further north to arms. With such co-operation the leaders believed they would

be competent to deal with all the royal forces north of Dublin, which would be compelled to draw

reinforcements from the troops then swarming in their native county. The hoped-for result was not

achieved, however, and the Wexfordmen, sorely disappointed, felt compelled to retrace their steps. In so doing

they divided into two columns, one of which marched directly south through central Meath. This was much

the stronger of the two forces. The lesser one, after re-crossing the river Boyne, marched in a more easterly

direction and entered Fingall.

They marched northwards as far as the village of Nobber, in county Meath, in the hope that they might arouse

Meath, Louth and counties further north to arms. With such co-operation the leaders believed they would

be competent to deal with all the royal forces north of Dublin, which would be compelled to draw

reinforcements from the troops then swarming in their native county. The hoped-for result was not

achieved, however, and the Wexfordmen, sorely disappointed, felt compelled to retrace their steps. In so doing

they divided into two columns, one of which marched directly south through central Meath. This was much

the stronger of the two forces. The lesser one, after re-crossing the river Boyne, marched in a more easterly

direction and entered Fingall.

Teeling devotes a chapter to the description of this northwards movement of the Wexford insurgents.

After describing the various occasions on which the rebel column asserted itself on the northward march,

the historian, in closing the chapter, thus writes of that portion of it which reached Fingall:

"Drogheda lay on their left. Slane to the right, and Navan a few miles higher up the river, in a more

westerly direction. From the British garrisons in these towns they encountered little interruption, and they entered the

metropolitan county with increasing feelings of confidence. But notwithstanding their gallant bearing,

fatigue, privation, the casualties of war and the expenditure of their ammunition had reduced this once

formidable column to a state bordering on defenceless.

Teeling devotes a chapter to the description of this northwards movement of the Wexford insurgents.

After describing the various occasions on which the rebel column asserted itself on the northward march,

the historian, in closing the chapter, thus writes of that portion of it which reached Fingall:

"Drogheda lay on their left. Slane to the right, and Navan a few miles higher up the river, in a more

westerly direction. From the British garrisons in these towns they encountered little interruption, and they entered the

metropolitan county with increasing feelings of confidence. But notwithstanding their gallant bearing,

fatigue, privation, the casualties of war and the expenditure of their ammunition had reduced this once

formidable column to a state bordering on defenceless.

Still they pressed forward with the hope of

entering Kildare, which four hours' march would now have effected. At this critical

moment they came in contact with the forces of the enemy, who intercepting their march at the village of

Ballyboughal, ten miles north of the capital, forced them into action and compelled them to a disorderly

retreat. The victory was decisive and the Wexford column was never again organised". Such is the

historian's brief description of the Wexford mens' fatal march into Fingall. The traditional account,

however, supplies further interesting

details of this historical tragedy.

According to tradition, the Wexford column, after crossing the river Delvin into Fingall at Ford-a-Fyne,

marched directly southwards on the road which crossed the western shoulder of Malahow hill.

Still they pressed forward with the hope of

entering Kildare, which four hours' march would now have effected. At this critical

moment they came in contact with the forces of the enemy, who intercepting their march at the village of

Ballyboughal, ten miles north of the capital, forced them into action and compelled them to a disorderly

retreat. The victory was decisive and the Wexford column was never again organised". Such is the

historian's brief description of the Wexford mens' fatal march into Fingall. The traditional account,

however, supplies further interesting

details of this historical tragedy.

According to tradition, the Wexford column, after crossing the river Delvin into Fingall at Ford-a-Fyne,

marched directly southwards on the road which crossed the western shoulder of Malahow hill.

About a

half-mile to the south of this hill the column swung south-east at a point near Springhill, where the

road forked. After passing through the townland of Trallie and into that of Wyanstown, it turned

directly eastwards at the next cross roads and continued in that direction till it made its final halt

at Drishogue Lane. The townlands through which it marched after leaving Wyanstown were those of

Leestown, Westpalstown and The Murragh. At Leestown, the travel-weary insurgents halted for a brief

rest, during which they partook of homely refreshment obtained from a farmhouse on the roadside. Their

strength at this juncture is said to have been considerably less than one hundred efficient men. Having

thus rested, and somewhat refreshed themselves, the Wexford men resumed their march eastwards on what

was destined to be the final stage of their long journeying.

About a

half-mile to the south of this hill the column swung south-east at a point near Springhill, where the

road forked. After passing through the townland of Trallie and into that of Wyanstown, it turned

directly eastwards at the next cross roads and continued in that direction till it made its final halt

at Drishogue Lane. The townlands through which it marched after leaving Wyanstown were those of

Leestown, Westpalstown and The Murragh. At Leestown, the travel-weary insurgents halted for a brief

rest, during which they partook of homely refreshment obtained from a farmhouse on the roadside. Their

strength at this juncture is said to have been considerably less than one hundred efficient men. Having

thus rested, and somewhat refreshed themselves, the Wexford men resumed their march eastwards on what

was destined to be the final stage of their long journeying.

Half an hour later in the townland of The

Murragh, they were overtaken by a pursuing force. This was a strong detachment if not the entire

strength, of the "Dumfries Light Dragoons", which according to local estimation consisted of about 500

troopers, well-armed and mounted.

On establishing contact, shots were exchanged between the two forces and the insurgents, for a distance

of about two furlongs, checked their pursuers by maintaining a rearguard action in which they expended

the greater part of their scanty remnant of ammunition. The harassed insurgents carried on this running

fight in the hope that somewhere further along the road they might find a favourable position in which

to make a determined stand. After holding their pursuers in check for the distance mentioned, the

insurgents arrived at a portion of the road which presented more protective features, and there they

halted to give battle for the last time.

Half an hour later in the townland of The

Murragh, they were overtaken by a pursuing force. This was a strong detachment if not the entire

strength, of the "Dumfries Light Dragoons", which according to local estimation consisted of about 500

troopers, well-armed and mounted.

On establishing contact, shots were exchanged between the two forces and the insurgents, for a distance

of about two furlongs, checked their pursuers by maintaining a rearguard action in which they expended

the greater part of their scanty remnant of ammunition. The harassed insurgents carried on this running

fight in the hope that somewhere further along the road they might find a favourable position in which

to make a determined stand. After holding their pursuers in check for the distance mentioned, the

insurgents arrived at a portion of the road which presented more protective features, and there they

halted to give battle for the last time.

The place where this halt was made is known locally as

Drishogue Lane, because of the road being there joined by a by-road which leads to the townland of

Drishogue and is situated within less than half a mile of Ballyboughal, which lies to the east. The road

which the Wexford men were pursuing here takes an abrupt turn to the right, to continue on a

semi-circular course almost in an arc for about fifty yards, when it again turns sharply to the right

for Ballyboughal. The junction with Drishogue Lane is

almost in the centre of this arc. The road fence on the left, or northern side of the arc described, consists

of a wall of stone and mortar which extends beyond the junction with Drishogue Lane. This wall rises some four

feet above the level of the road, but has a drop of at least sixteen feet on its northern face (in consequence

of the land being low-lying on that side), which strong barrier gave perfect protection to the right flank of

the Wexford men when they halted and faced westwards to meet the onslaught of the British dragoons.

The place where this halt was made is known locally as

Drishogue Lane, because of the road being there joined by a by-road which leads to the townland of

Drishogue and is situated within less than half a mile of Ballyboughal, which lies to the east. The road

which the Wexford men were pursuing here takes an abrupt turn to the right, to continue on a

semi-circular course almost in an arc for about fifty yards, when it again turns sharply to the right

for Ballyboughal. The junction with Drishogue Lane is

almost in the centre of this arc. The road fence on the left, or northern side of the arc described, consists

of a wall of stone and mortar which extends beyond the junction with Drishogue Lane. This wall rises some four

feet above the level of the road, but has a drop of at least sixteen feet on its northern face (in consequence

of the land being low-lying on that side), which strong barrier gave perfect protection to the right flank of

the Wexford men when they halted and faced westwards to meet the onslaught of the British dragoons.

The roadside field on that portion of the arc east of the junction was then

at that point some five feet above

the roadway, and inside the fence of this field about a dozen insurgent musketeers took up a position which commanded

at about twenty-five yards range the abrupt turn which they had lately rounded. When the dragoons in turn were

rounding this point, they were received by a volley which the musketeers fired over the heads of their comrades,

who were drawn up on the roadway with pikes advanced in preparation for the expected cavalry charge. Some saddles

were emptied by the rebel fire, and the pursuing force halted momentarily, its front ranks retiring behind the turn,

and so out of sight of the rebel musketeers. The dragoons, however, had they but known it, were in no danger of a

further fusillade. The volley which caused them to recoil was the rebels' final fire. They had no more ammunition.

Only the steel remained, and so, with pikes advanced, the Wexford men awaited the next move of the dragoons.

The roadside field on that portion of the arc east of the junction was then

at that point some five feet above

the roadway, and inside the fence of this field about a dozen insurgent musketeers took up a position which commanded

at about twenty-five yards range the abrupt turn which they had lately rounded. When the dragoons in turn were

rounding this point, they were received by a volley which the musketeers fired over the heads of their comrades,

who were drawn up on the roadway with pikes advanced in preparation for the expected cavalry charge. Some saddles

were emptied by the rebel fire, and the pursuing force halted momentarily, its front ranks retiring behind the turn,

and so out of sight of the rebel musketeers. The dragoons, however, had they but known it, were in no danger of a

further fusillade. The volley which caused them to recoil was the rebels' final fire. They had no more ammunition.

Only the steel remained, and so, with pikes advanced, the Wexford men awaited the next move of the dragoons.

It came

soon, and from an unexpected quarter. A number of troopers from the rearward ranks of the pursuing force entered the

field on their right flank. Screened by the roadside hedge, they advanced along it to that point where it formed

portion of the arc. From this position at a few yards range they poured a deadly fire into the closely formed

ranks of the insurgents. A second volley followed, and immediately the Dumfries' main force on the roadway charged

the gapped ranks of the rebel phalanx.

The depleted Wexford force met the shock bravely, but the pikes, though taking a toll of the enemy, failed to stem the charge. Resistance,

though desperate, proved unavailing. The weakened remnant of the once formidable Wexford column was overwhelmed, and after

a few minutes of merciless slaughter it was represented only by the dead and dying, save for a few who at the last moment

sought in flight escape from certain death at the hands of foes who gave no quarter.

It came

soon, and from an unexpected quarter. A number of troopers from the rearward ranks of the pursuing force entered the

field on their right flank. Screened by the roadside hedge, they advanced along it to that point where it formed

portion of the arc. From this position at a few yards range they poured a deadly fire into the closely formed

ranks of the insurgents. A second volley followed, and immediately the Dumfries' main force on the roadway charged

the gapped ranks of the rebel phalanx.

The depleted Wexford force met the shock bravely, but the pikes, though taking a toll of the enemy, failed to stem the charge. Resistance,

though desperate, proved unavailing. The weakened remnant of the once formidable Wexford column was overwhelmed, and after

a few minutes of merciless slaughter it was represented only by the dead and dying, save for a few who at the last moment

sought in flight escape from certain death at the hands of foes who gave no quarter.

The fight in which the depleted Wexford

column was annihilated - according to accounts - lasted less than ten minutes. Of these latter some half-dozen or thereabouts

who took to the fields on the northern side, where the nature of the ground precluded immediate pursuit by cavalry, escaped

and found refuge as farm labourers with various families in the neighbourhood, until such time as they considered it safe to

return to their native county of Wexford. It was from these men that the details of their last stand at Drishogue Lane were learned.

Details which,

preserved in local tradition, enabled the writer to describe an event of which historians seem to have had but little information.

The victorious dragoons removed their dead and wounded to some destination unknown to tradition, but the bodies of the slain Wexford

men were left where they fell.

The fight in which the depleted Wexford

column was annihilated - according to accounts - lasted less than ten minutes. Of these latter some half-dozen or thereabouts

who took to the fields on the northern side, where the nature of the ground precluded immediate pursuit by cavalry, escaped

and found refuge as farm labourers with various families in the neighbourhood, until such time as they considered it safe to

return to their native county of Wexford. It was from these men that the details of their last stand at Drishogue Lane were learned.

Details which,

preserved in local tradition, enabled the writer to describe an event of which historians seem to have had but little information.

The victorious dragoons removed their dead and wounded to some destination unknown to tradition, but the bodies of the slain Wexford

men were left where they fell.

On the evening of the following day, numbers of the local inhabitants assembled and conveyed these

latter to the old churchyard of Ballyboughal, where they were interred coffinless. The task proved so laborious that by nightfall

it was still not completed. Under the conditions the workers were constrained to consign several bodies to each of the graves which were

made. Notwithstanding this action, it was found that the graves did not provide sufficient accommodation for the dead, and so some

dozen of the corpses were placed in an old vault or subterranean chamber adjoining the church ruins, the entrance to which was then

blocked with stones and earth. After a number of years this barrier disintegrated and access could be had to the vault. Over fifty

years ago there were many bones and about a dozen skulls in this vault, in two or three of which latter were bullet holes, while

others evidenced the downward slash of the sabre. Visited recently, only a few bones and three skulls were to be seen, the remainder

in the passage of half a century having apparently crumbled into dust.

On the evening of the following day, numbers of the local inhabitants assembled and conveyed these

latter to the old churchyard of Ballyboughal, where they were interred coffinless. The task proved so laborious that by nightfall

it was still not completed. Under the conditions the workers were constrained to consign several bodies to each of the graves which were

made. Notwithstanding this action, it was found that the graves did not provide sufficient accommodation for the dead, and so some

dozen of the corpses were placed in an old vault or subterranean chamber adjoining the church ruins, the entrance to which was then

blocked with stones and earth. After a number of years this barrier disintegrated and access could be had to the vault. Over fifty

years ago there were many bones and about a dozen skulls in this vault, in two or three of which latter were bullet holes, while

others evidenced the downward slash of the sabre. Visited recently, only a few bones and three skulls were to be seen, the remainder

in the passage of half a century having apparently crumbled into dust.

This account of a solitary Wexford man's last stand was frequently borne out by a woman of the neighbourhood who was twelve years old in 1798

and lived to recount her experience for another seventy-four years: On the day in question she had been sent from her home in Drishogue

on a shopping errand to Ballyboughal. When returning to her home all was quiet at the road junction which soon later was to become the

scene of such slaughter. Proceeding along Drishogue Lane to her home, not more than fifteen minutes walk distant, she delayed a little when near her

residence, to pick some early blackberries on

the wayside. (The blackberries ripened early in 1798 because of a prolonged period of fine Summer weather). She was then about half a mile distant

from the road junction. While engaged in picking the blackberries, she was startled

to observe a man come running around a turn some forty yards behind her on the road she had just traversed.

This account of a solitary Wexford man's last stand was frequently borne out by a woman of the neighbourhood who was twelve years old in 1798

and lived to recount her experience for another seventy-four years: On the day in question she had been sent from her home in Drishogue

on a shopping errand to Ballyboughal. When returning to her home all was quiet at the road junction which soon later was to become the

scene of such slaughter. Proceeding along Drishogue Lane to her home, not more than fifteen minutes walk distant, she delayed a little when near her

residence, to pick some early blackberries on

the wayside. (The blackberries ripened early in 1798 because of a prolonged period of fine Summer weather). She was then about half a mile distant

from the road junction. While engaged in picking the blackberries, she was startled

to observe a man come running around a turn some forty yards behind her on the road she had just traversed.

As the man rapidly approached

she noticed with alarm that there was blood on his face and also that he carried a blood-stained pike in his hand. She was much further

alarmed, however, when a second or two later she saw two troopers come galloping around the turn in pursuit of the pikeman. "Frightened

out of her wits", as she was accustomed to say, she jumped into the "ditch of briars" on the roadside. Crouching, she was relieved to

find that none of the armed men came as far as the position she occupied. Her quick ears informed her that the pikeman had jumped

across the ditch in which she crouched at a few yards distance, and glancing through the briars, she saw that the fugitive had gained

the field, and with his back to the roadway was running at full speed. Almost immediately she heard the troopers bring their horses

to a sudden halt and a second or two later the wrenching open of a gate which gave passage to the field in which the pikeman was

running, in the belief probably that he had placed an effective barrier between himself and his foes, when he jumped the ditch.

As the man rapidly approached

she noticed with alarm that there was blood on his face and also that he carried a blood-stained pike in his hand. She was much further

alarmed, however, when a second or two later she saw two troopers come galloping around the turn in pursuit of the pikeman. "Frightened

out of her wits", as she was accustomed to say, she jumped into the "ditch of briars" on the roadside. Crouching, she was relieved to

find that none of the armed men came as far as the position she occupied. Her quick ears informed her that the pikeman had jumped

across the ditch in which she crouched at a few yards distance, and glancing through the briars, she saw that the fugitive had gained

the field, and with his back to the roadway was running at full speed. Almost immediately she heard the troopers bring their horses

to a sudden halt and a second or two later the wrenching open of a gate which gave passage to the field in which the pikeman was

running, in the belief probably that he had placed an effective barrier between himself and his foes, when he jumped the ditch.

Gazing from her hiding place, the young girl saw the troopers galloping across the field in hot pursuit of the pikeman. A few seconds sufficed to bring them within twenty yards

of the fugitive. Another few strides of the chargers and "I'll see the poor man cut to pieces" was the thought of the terrified spectator.

Such was not to be the manner of the lone Wexford man's death, however. Glancing backwards as he ran, he perceived that his enemies were close upon

him. He immediately halted and with pike presented faced the oncoming dragoons. Watching with horrified interest, the onlooker felt a

thrill of admiration for the hunted man who thus boldly faced his pursuers, and all her sympathy went out to him. To her relief she saw

the troopers rein in their chargers when within a dozen yards of the waiting pikeman, and she prayed that he might win through and escape,

but her feeling of relief was of short duration. The troopers had not, as she thought, desisted from the chase.

Gazing from her hiding place, the young girl saw the troopers galloping across the field in hot pursuit of the pikeman. A few seconds sufficed to bring them within twenty yards

of the fugitive. Another few strides of the chargers and "I'll see the poor man cut to pieces" was the thought of the terrified spectator.

Such was not to be the manner of the lone Wexford man's death, however. Glancing backwards as he ran, he perceived that his enemies were close upon

him. He immediately halted and with pike presented faced the oncoming dragoons. Watching with horrified interest, the onlooker felt a

thrill of admiration for the hunted man who thus boldly faced his pursuers, and all her sympathy went out to him. To her relief she saw

the troopers rein in their chargers when within a dozen yards of the waiting pikeman, and she prayed that he might win through and escape,

but her feeling of relief was of short duration. The troopers had not, as she thought, desisted from the chase.

A second or two later she

understood the meaning of their sudden halt. They evidently had little relish for opposing their own steel to the dreaded pike. She noticed

a sudden transfer of the drawn sabres to the bridle hands of the dragoons, and then to her dismay she saw pistols drawn from holsters and

levelled at the pikeman. She wanted to close her eyes as the shots were discharged, but somehow found herself compelled to witness the

closing details of the tragedy. As the pistol-shots rang out, she saw the pikeman spring forward towards his assailants. Then

he staggered as if about to fall, but recovered and stood with his weapon advanced as if challenging the troopers to close with him. But

these warriors had no intention of coming to close quarters with the lone pikeman.

A second or two later she

understood the meaning of their sudden halt. They evidently had little relish for opposing their own steel to the dreaded pike. She noticed

a sudden transfer of the drawn sabres to the bridle hands of the dragoons, and then to her dismay she saw pistols drawn from holsters and

levelled at the pikeman. She wanted to close her eyes as the shots were discharged, but somehow found herself compelled to witness the

closing details of the tragedy. As the pistol-shots rang out, she saw the pikeman spring forward towards his assailants. Then

he staggered as if about to fall, but recovered and stood with his weapon advanced as if challenging the troopers to close with him. But

these warriors had no intention of coming to close quarters with the lone pikeman.

Drawing their two remaining pistols they took careful

aim and again fired. The Wexford man sagged, tried to sustain himself with his pike-shaft but failing in the effort fell forward,

apparently lifeless. Then the dragoons rode boldly towards the fallen man, and bending in their saddles sabred him as he lay bleeding

on the green sward.

From this account it can be gathered, if there were no further knowledge available, that the conflict at the road junction was of very

short duration. It may be remarked that the girl, who thus passed the junction some short time before the insurgents halted there, heard

no sounds of shooting while completing her homeward journey, which she was wont to explain by stating that there was a strong southerly

wind on that day which prevented the noise of the fight from coming in her direction.

Drawing their two remaining pistols they took careful

aim and again fired. The Wexford man sagged, tried to sustain himself with his pike-shaft but failing in the effort fell forward,

apparently lifeless. Then the dragoons rode boldly towards the fallen man, and bending in their saddles sabred him as he lay bleeding

on the green sward.

From this account it can be gathered, if there were no further knowledge available, that the conflict at the road junction was of very

short duration. It may be remarked that the girl, who thus passed the junction some short time before the insurgents halted there, heard

no sounds of shooting while completing her homeward journey, which she was wont to explain by stating that there was a strong southerly

wind on that day which prevented the noise of the fight from coming in her direction.

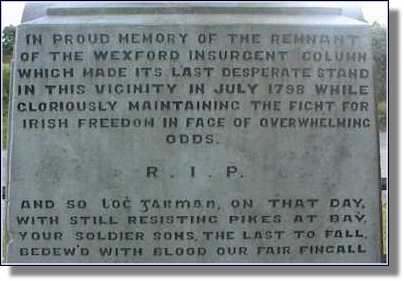

Inscription on the base of the memorial erected in 1948

Inscription on the base of the memorial erected in 1948

at Drishogue Lane, to mark the 150th anniversary

of the

1798 Rebellion, and the last stand of the United Irish rebels.

"Loc Garman" is Wexford in the

Irish (Gaelic) language.

Click on the picture for another view of the monument.

When the Wexford men entered Fingall it was observed that many of them were wounded, and had

to be supported by their comrades on the

march. Some of these latter were fatigued to the verge of exhaustion, and therefore ill prepared to oppose fresh adversaries. An incident

of the march which occurred soon after the column entered Fingall is worth recording, if only to confute the historian already quoted,

who would have his readers believe that the local insurgents, while marching westwards on 23 May, "plundered and destroyed the house of

every Protestant" along six miles of the road leading from Westpalstown to Garristown. The Wexford column within the first two miles

of its march in Fingall entered upon this road at Springhill.

At this point one of the wounded insurgents named Walsh, unable to proceed further, sought refuge in a respectable farmer's home adjoining

the road.

When the Wexford men entered Fingall it was observed that many of them were wounded, and had

to be supported by their comrades on the

march. Some of these latter were fatigued to the verge of exhaustion, and therefore ill prepared to oppose fresh adversaries. An incident

of the march which occurred soon after the column entered Fingall is worth recording, if only to confute the historian already quoted,

who would have his readers believe that the local insurgents, while marching westwards on 23 May, "plundered and destroyed the house of

every Protestant" along six miles of the road leading from Westpalstown to Garristown. The Wexford column within the first two miles

of its march in Fingall entered upon this road at Springhill.

At this point one of the wounded insurgents named Walsh, unable to proceed further, sought refuge in a respectable farmer's home adjoining

the road.

Walsh was received with every kindness and nursed back to health. When he was fully recovered,

the family which gave him refuge

kept him in the capacity of farm hand for a lengthened period, until he was able to return in safety to his home. The house in which the

Wexford rebel was thus succoured was one of the Protestant homes which Musgrave tells us were destroyed by the Fingallian insurgents two

months previously. This incident goes to prove Musgrave's mendacity. Had the house been destroyed as stated, it could hardly have been

rebuilt and occupied in the short period of two months, particularly considering the disturbed state of the country. Even should this

have been done, it would hardly be expected that the family which occupied it would feel disposed to harbour unlawfully a member of

the rebel forces which had previously rendered it homeless.

Walsh was received with every kindness and nursed back to health. When he was fully recovered,

the family which gave him refuge

kept him in the capacity of farm hand for a lengthened period, until he was able to return in safety to his home. The house in which the

Wexford rebel was thus succoured was one of the Protestant homes which Musgrave tells us were destroyed by the Fingallian insurgents two

months previously. This incident goes to prove Musgrave's mendacity. Had the house been destroyed as stated, it could hardly have been

rebuilt and occupied in the short period of two months, particularly considering the disturbed state of the country. Even should this

have been done, it would hardly be expected that the family which occupied it would feel disposed to harbour unlawfully a member of

the rebel forces which had previously rendered it homeless.

The name of Wilson, that of the kindly Protestant family alluded to, deserves to be recorded

here. Like other families of the same religion

in the locality, the members of it ever displayed friendliness towards their Catholic neighbours, whom it may be mentioned reciprocated

the feeling. It may also be recorded in honour of some of these Protestant families who happened to have influence with the Government

forces, that they interested themselves actively and successfully, after the fight at Tara, in saving the lives of local insurgents who

participated in that conflict and were, after their homecoming, arrested on suspicion of having borne arms against the Crown. It may be

of further interest to relate that some fifty years after the rebel Walsh departed from the Wilson homestead, another link was forged

between him and Fingall.

This was the arrival of a priest to take charge of the united parishes of Rowlestown and Oldtown, the latter of which adjoins the parish

in which Walsh was harboured.

The name of Wilson, that of the kindly Protestant family alluded to, deserves to be recorded

here. Like other families of the same religion

in the locality, the members of it ever displayed friendliness towards their Catholic neighbours, whom it may be mentioned reciprocated

the feeling. It may also be recorded in honour of some of these Protestant families who happened to have influence with the Government

forces, that they interested themselves actively and successfully, after the fight at Tara, in saving the lives of local insurgents who

participated in that conflict and were, after their homecoming, arrested on suspicion of having borne arms against the Crown. It may be

of further interest to relate that some fifty years after the rebel Walsh departed from the Wilson homestead, another link was forged

between him and Fingall.

This was the arrival of a priest to take charge of the united parishes of Rowlestown and Oldtown, the latter of which adjoins the parish

in which Walsh was harboured.

The new parish priest lost little time in informing his parishioners that he was the son

of the rebel named

Walsh whom the Wilsons of Springhill had succoured in 1798. Father Walsh visited the Wilson family on the day following that of his arrival

in Fingall, and introduced himself as the son of the rebel their home had sheltered. He was as kindly received by the younger generation

of the family as his father had been by their forebears in 1798, and from that moment up to the time of his death Father Walsh maintained

a most friendly relationship with the family. Tradition supplies us with no further details concerning the Wexford column, and as it

does not exactly agree with the historical record quoted, some comparison is necessary.

The new parish priest lost little time in informing his parishioners that he was the son

of the rebel named

Walsh whom the Wilsons of Springhill had succoured in 1798. Father Walsh visited the Wilson family on the day following that of his arrival

in Fingall, and introduced himself as the son of the rebel their home had sheltered. He was as kindly received by the younger generation

of the family as his father had been by their forebears in 1798, and from that moment up to the time of his death Father Walsh maintained

a most friendly relationship with the family. Tradition supplies us with no further details concerning the Wexford column, and as it

does not exactly agree with the historical record quoted, some comparison is necessary.

The historian Teeling describes the Wexford men on their arrival in the metropolitan county as

pressing forward with the hope of entering

Kildare, from which they were about four hours' march when intercepted near the village of Ballyboughal. The historian makes no mention of the

exact line of march pursued by the column on entering Fingall. Tradition, on the other hand, is quite definite. It tells us plainly how and

where the Wexford men were overtaken. How the insurgents could be pressing towards Kildare when the last stage of their march was directly

eastwards towards the sea seems incomprehensible. Their route for the first two miles in Fingallian territory accords with the historical

statement, but the remainder of their march seems irreconcilable with it. From that point where they first swung eastwards they were

increasing the distance between themselves and Kildare with every step they took.

The historian Teeling describes the Wexford men on their arrival in the metropolitan county as

pressing forward with the hope of entering

Kildare, from which they were about four hours' march when intercepted near the village of Ballyboughal. The historian makes no mention of the

exact line of march pursued by the column on entering Fingall. Tradition, on the other hand, is quite definite. It tells us plainly how and

where the Wexford men were overtaken. How the insurgents could be pressing towards Kildare when the last stage of their march was directly

eastwards towards the sea seems incomprehensible. Their route for the first two miles in Fingallian territory accords with the historical

statement, but the remainder of their march seems irreconcilable with it. From that point where they first swung eastwards they were

increasing the distance between themselves and Kildare with every step they took.

What impelled them to thus deviate from the direct

course to their objective has never been adequately explained. The leaders could not possibly have lost their sense of direction, inasmuch as the

coastline of Fingall, clearly indicated by the bold landmarks of Lambay Island, Ireland's Eye and Howth Head, was easily discernible from the

high ground over which the column had passed prior to swinging eastwards. That the insurgents were not hurriedly diverted from the

southern route by the apprehension of imminent danger was evidenced by their easy bearing when they halted and rested for a while

at Leestown.

The policy of the Wexford men at this juncture was, for obvious reasons, to avoid marching on main roads or through towns or villages, and

more than likely it was in pursuance of this policy that they marched eastwards into the heart of Fingall. The direct southern route,

from the point at which they abandoned it, would, as their obvious line of march, become more dangerous as they proceeded.

What impelled them to thus deviate from the direct

course to their objective has never been adequately explained. The leaders could not possibly have lost their sense of direction, inasmuch as the

coastline of Fingall, clearly indicated by the bold landmarks of Lambay Island, Ireland's Eye and Howth Head, was easily discernible from the

high ground over which the column had passed prior to swinging eastwards. That the insurgents were not hurriedly diverted from the

southern route by the apprehension of imminent danger was evidenced by their easy bearing when they halted and rested for a while

at Leestown.

The policy of the Wexford men at this juncture was, for obvious reasons, to avoid marching on main roads or through towns or villages, and

more than likely it was in pursuance of this policy that they marched eastwards into the heart of Fingall. The direct southern route,

from the point at which they abandoned it, would, as their obvious line of march, become more dangerous as they proceeded.

It was almost

certain that all the roads between them and Kildare were well patrolled by strong forces of the enemy. Military stations at Ratoath and

Dunboyne also lay in that direction. Though not mentioned in tradition, it is quite possible that some local sympathiser advised them

of these dangers and also indicated an alternative route which did not lead by military stations. This route, mainly confined to bye-roads

and consequently not likely to be patrolled, led for the greater part of its course through the centre of Fingall in a southerly direction.

It may be conjectured that the military authorities, being satisfied that the rebel column would hardly dare to venture thus close to

Dublin city, did not guard this route, and so left open a line of march which the insurgents, acting on local information, decided to

follow.

It was almost

certain that all the roads between them and Kildare were well patrolled by strong forces of the enemy. Military stations at Ratoath and

Dunboyne also lay in that direction. Though not mentioned in tradition, it is quite possible that some local sympathiser advised them

of these dangers and also indicated an alternative route which did not lead by military stations. This route, mainly confined to bye-roads

and consequently not likely to be patrolled, led for the greater part of its course through the centre of Fingall in a southerly direction.

It may be conjectured that the military authorities, being satisfied that the rebel column would hardly dare to venture thus close to

Dublin city, did not guard this route, and so left open a line of march which the insurgents, acting on local information, decided to

follow.

Such is the only explanation that can be offered for the apparently aimless march of the Wexford column to the eastward in

Fingall, as described. The remainder of the assumed alternative route would have been by a line of by-roads passing southwards through

Drishogue, Scatternagh, Lispopple, Mount Ambrose, Surgalstown, Tubberburr and Huntstown to the village of Saint Margaret's, a distance

of eight miles. From Saint Margaret's for half a mile southwards the route would be on a main road. After that distance, however, the

route would again be along by-roads leading towards Kildare, by way of Dunsoughly, Cloghran, Mulhuddart and Clonsilla.

Such is the only explanation that can be offered for the apparently aimless march of the Wexford column to the eastward in

Fingall, as described. The remainder of the assumed alternative route would have been by a line of by-roads passing southwards through

Drishogue, Scatternagh, Lispopple, Mount Ambrose, Surgalstown, Tubberburr and Huntstown to the village of Saint Margaret's, a distance

of eight miles. From Saint Margaret's for half a mile southwards the route would be on a main road. After that distance, however, the

route would again be along by-roads leading towards Kildare, by way of Dunsoughly, Cloghran, Mulhuddart and Clonsilla.

The British administration in Dublin Castle breathed a sigh of relief when the Rebellion was finally crushed, after three long months of

fierce fighting, atrocities and reprisals. Lord Castlereagh admonished an English friend at the time: "I understand you are inclined to hold the Insurrection cheap. Rely upon it; there

never was in any country so formidable an effort on the part of the people..."

The British administration in Dublin Castle breathed a sigh of relief when the Rebellion was finally crushed, after three long months of

fierce fighting, atrocities and reprisals. Lord Castlereagh admonished an English friend at the time: "I understand you are inclined to hold the Insurrection cheap. Rely upon it; there

never was in any country so formidable an effort on the part of the people..."

Webmaster's note:

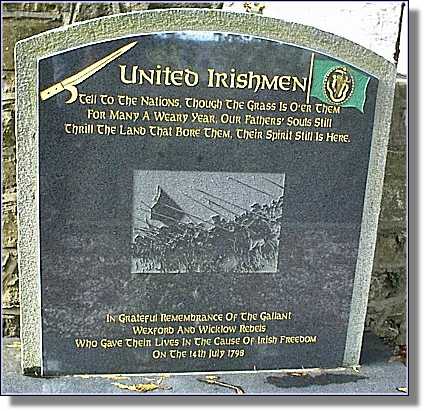

The plaque above, which was unveiled on July 14th, 1998, in the old churchyard at Ballyboughal, says everything about the respect and reverence in which these brave men are still held

today, more than two hundred years after their courageous sacrifice on that small roadway in north County Dublin. To the English administration of the time, it must

have

seemed as though they had finally triumphed over what was seen as yet another attempt to wrest away from them one of their oldest-established colonies.

What they failed to recognise and to acknowledge was that the blood of these men, like those who were executed following the Easter Rising of 1916,

would nourish and renew the roots of the Tree of Liberty, which grew and transformed itself into the strong, prosperous and independent nation of today.

Without their selflessness, their valour and their bravery, we would not have the freedom and democracy which we all too often take for granted, and I,

like the sculptor who carved this plaque and made no charge for his tribute in stone, salute their gallant efforts in their final battle at Drishogue Lane.

"Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anamacha"

(May their souls be on the right hand of God.")

The plaque above, which was unveiled on July 14th, 1998, in the old churchyard at Ballyboughal, says everything about the respect and reverence in which these brave men are still held

today, more than two hundred years after their courageous sacrifice on that small roadway in north County Dublin. To the English administration of the time, it must

have

seemed as though they had finally triumphed over what was seen as yet another attempt to wrest away from them one of their oldest-established colonies.

What they failed to recognise and to acknowledge was that the blood of these men, like those who were executed following the Easter Rising of 1916,

would nourish and renew the roots of the Tree of Liberty, which grew and transformed itself into the strong, prosperous and independent nation of today.

Without their selflessness, their valour and their bravery, we would not have the freedom and democracy which we all too often take for granted, and I,

like the sculptor who carved this plaque and made no charge for his tribute in stone, salute their gallant efforts in their final battle at Drishogue Lane.

"Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anamacha"

(May their souls be on the right hand of God.")

![]()

![]()