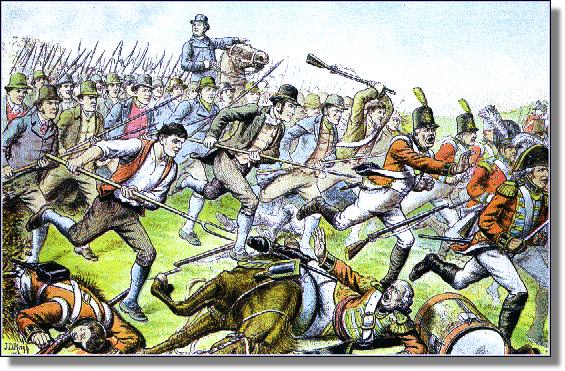

Intelligently led by Morgan Byrne, Edward Roche, George Sparks and Father John Murphy of Boolavogue, the United Irish army achieved a

shattering victory over the North Cork Militia on Oulart Hill, in County Wexford, on Whit Sunday, May 27th, 1798. Publicly "Orange", and recruited from

converts on the Mitchelstown estate, they were led by the arrogant sexual predator Lord Kingsborough. The North Corks were much hated,

especially after they introduced "pitchcapping", by which an inflammable mixture of pitch and gunpowder was jammed onto the victim's head

and set alight. The rebels' victory was a stunning vindication of the pike's effectiveness against a cavalry charge on well-chosen ground.

The enclosed Wexford countryside was dangerous for cavalry who could never get a clear sight of the enemy, and who were therefore extremely

vulnerable to well-executed ambushes such as this one, by rebels who were very familiar with the locality. Of the one hundred and ten red-coated Yeomen

who marched so confidently up the hillside that day, just five survived the slaughter which lit the flame of rebellion whose light

illuminated the pathway towards Ireland's eventual and long-fought-for liberty.

Intelligently led by Morgan Byrne, Edward Roche, George Sparks and Father John Murphy of Boolavogue, the United Irish army achieved a

shattering victory over the North Cork Militia on Oulart Hill, in County Wexford, on Whit Sunday, May 27th, 1798. Publicly "Orange", and recruited from

converts on the Mitchelstown estate, they were led by the arrogant sexual predator Lord Kingsborough. The North Corks were much hated,

especially after they introduced "pitchcapping", by which an inflammable mixture of pitch and gunpowder was jammed onto the victim's head

and set alight. The rebels' victory was a stunning vindication of the pike's effectiveness against a cavalry charge on well-chosen ground.

The enclosed Wexford countryside was dangerous for cavalry who could never get a clear sight of the enemy, and who were therefore extremely

vulnerable to well-executed ambushes such as this one, by rebels who were very familiar with the locality. Of the one hundred and ten red-coated Yeomen

who marched so confidently up the hillside that day, just five survived the slaughter which lit the flame of rebellion whose light

illuminated the pathway towards Ireland's eventual and long-fought-for liberty.

On hearing of the news of the mid-Wexford rising, a 110-strong force of the North Cork Militia had marched from Wexford town, determined to put down

the insurgency with a swift strike. The arrival of this militia outfit was every Catholic's nightmare. The North Corks were certain that mere "croppies"

-- many armed only with stones -- would not stand against fully equipped troops. Nonetheless, the notorious militiamen approached the battleground leaving burning cabins in their

wake, a cruel attempt to frighten the assembled peasants off Oulart Hill. But although Father Murphy's rag-tag army, now grown to over a thousand,

could clearly track the approaching militiamen by the smoke, the insurgents calmly stood their ground. Armed with pikes, scythes, hay-forks and about forty muskets,

they quietly awaited the arrival of the living embodiment of their most fearsome dreams. By three o'clock in the afternoon the North Corks could be seen

on the roadway below Oulart Hill, spreading out in line-of-battle across the fields. As the militiamen advanced on the hill, Father John pointed out the red-coated

cavalry and infantry units and gave his men their orders: "They will wait to see us dispersed by the foot troops, so that their cavalry can fall on us

and cut us to pieces. Remain firm, together! We will surely defeat the infantry, and then will have nothing to fear from the cavalry."

On hearing of the news of the mid-Wexford rising, a 110-strong force of the North Cork Militia had marched from Wexford town, determined to put down

the insurgency with a swift strike. The arrival of this militia outfit was every Catholic's nightmare. The North Corks were certain that mere "croppies"

-- many armed only with stones -- would not stand against fully equipped troops. Nonetheless, the notorious militiamen approached the battleground leaving burning cabins in their

wake, a cruel attempt to frighten the assembled peasants off Oulart Hill. But although Father Murphy's rag-tag army, now grown to over a thousand,

could clearly track the approaching militiamen by the smoke, the insurgents calmly stood their ground. Armed with pikes, scythes, hay-forks and about forty muskets,

they quietly awaited the arrival of the living embodiment of their most fearsome dreams. By three o'clock in the afternoon the North Corks could be seen

on the roadway below Oulart Hill, spreading out in line-of-battle across the fields. As the militiamen advanced on the hill, Father John pointed out the red-coated

cavalry and infantry units and gave his men their orders: "They will wait to see us dispersed by the foot troops, so that their cavalry can fall on us

and cut us to pieces. Remain firm, together! We will surely defeat the infantry, and then will have nothing to fear from the cavalry."

Moments later,

red-hot musket balls were whistling among the Irish ranks. A rebel rushed forward, armed only with stones, and killed a reloading militiaman. The rebel

muskets roared. The militia advanced across the field, heading for the direction from which the fire had come. At that instant, led by Father John,

a mass of hidden pikemen leapt from behind the ditches on the North Corks' left flank. The militiamen were soon completely overrun, and must have seen

their fate written in the pent-up hatred on the rebels' faces. They turned and fled for their lives, spilling down the slopes from where they had come just

a few minutes before. Some ran for miles before being overtaken, impaled and gutted. They begged for mercy in both Gaelic and English. They blessed

themselves and shouted out prayers, since many of their number were themselves Catholic, but received absolutely no pity from the rebels. To the insurgents,

the men begging for their lives were the same ones who had so recently burned out and murdered their neighbours and friends. The merciless pikemen

offered no quarter, and the detested North Cork Militia disappeared forever on the bloody slopes of Oulart Hill.

Moments later,

red-hot musket balls were whistling among the Irish ranks. A rebel rushed forward, armed only with stones, and killed a reloading militiaman. The rebel

muskets roared. The militia advanced across the field, heading for the direction from which the fire had come. At that instant, led by Father John,

a mass of hidden pikemen leapt from behind the ditches on the North Corks' left flank. The militiamen were soon completely overrun, and must have seen

their fate written in the pent-up hatred on the rebels' faces. They turned and fled for their lives, spilling down the slopes from where they had come just

a few minutes before. Some ran for miles before being overtaken, impaled and gutted. They begged for mercy in both Gaelic and English. They blessed

themselves and shouted out prayers, since many of their number were themselves Catholic, but received absolutely no pity from the rebels. To the insurgents,

the men begging for their lives were the same ones who had so recently burned out and murdered their neighbours and friends. The merciless pikemen

offered no quarter, and the detested North Cork Militia disappeared forever on the bloody slopes of Oulart Hill.

Some hours later, Colonel Foote, a sergeant and three privates staggered back into Wexford town, all that was left of the command. There might have been

a sixth survivor but for a local woman who felled a fleeing militiaman with a single blow from an iron skillet.

The effect of the action at Oulart Hill on the surrounding countryside was electric. Father Murphy and his men had set up an intricate and highly effective

ambush, and had annihilated the most hated military unit in all of County Wexford, at the cost of only six rebel dead, and had given the insurgent Irish

what any rebellion badly needs at its outset -- an early victory. New volunteers in their thousands, armed with sickles, slash-hooks, and pitch-forks

swarmed to join the rebel priest and his peasant army.

Some hours later, Colonel Foote, a sergeant and three privates staggered back into Wexford town, all that was left of the command. There might have been

a sixth survivor but for a local woman who felled a fleeing militiaman with a single blow from an iron skillet.

The effect of the action at Oulart Hill on the surrounding countryside was electric. Father Murphy and his men had set up an intricate and highly effective

ambush, and had annihilated the most hated military unit in all of County Wexford, at the cost of only six rebel dead, and had given the insurgent Irish

what any rebellion badly needs at its outset -- an early victory. New volunteers in their thousands, armed with sickles, slash-hooks, and pitch-forks

swarmed to join the rebel priest and his peasant army.

![]()

![]()

![]()