Covering an

area

of one acre, Newgrange is one of the most impressive prehistoric monuments in

Europe. The

entrance, which is almost sixty feet (18.5 metres) long,

leads to the main chamber, which has a

corbelled roof and rises to a height of nineteen feet. The traditional name for

Newgrange and the grouping of tombs

to which it belongs, was

Brúgh na Bóinne

, and it was regarded in legend as the otherworld dwelling of the divine

Aonghus Mac Óg, or Aonghus the Youthful.

A thousand years older than Stonehenge, the giant megalithic tomb of Newgrange was probably

erected about

3,200 B.C.

in calendar years. It is one of a group of 40 passage tombs

including Knowth

and Dowth, that are enclosed on three sides by the river Boyne.

Passage tombs

are generally found in clusters giving rise to the theory that they

were

ancient cemeteries, perhaps for leading families. They consist essentially of a

round mound or

cairn

with a long, stone lined passage leading from the

outside

to a

chamber within.

Covering an

area

of one acre, Newgrange is one of the most impressive prehistoric monuments in

Europe. The

entrance, which is almost sixty feet (18.5 metres) long,

leads to the main chamber, which has a

corbelled roof and rises to a height of nineteen feet. The traditional name for

Newgrange and the grouping of tombs

to which it belongs, was

Brúgh na Bóinne

, and it was regarded in legend as the otherworld dwelling of the divine

Aonghus Mac Óg, or Aonghus the Youthful.

A thousand years older than Stonehenge, the giant megalithic tomb of Newgrange was probably

erected about

3,200 B.C.

in calendar years. It is one of a group of 40 passage tombs

including Knowth

and Dowth, that are enclosed on three sides by the river Boyne.

Passage tombs

are generally found in clusters giving rise to the theory that they

were

ancient cemeteries, perhaps for leading families. They consist essentially of a

round mound or

cairn

with a long, stone lined passage leading from the

outside

to a

chamber within.

As with Newgrange, which can still be seen with the naked eye from the Hill of

Tara, some 15 miles (10 kilometres) away, they tend to be situated

on hill tops

and commanding sites. The mound is enclosed on the outside by a

circle of standing stones

of which twelve remain. This gives the impression that the

monument

was built

and designed to stand out from the landscape - perhaps as a beacon for pagan

worship. The present day reconstruction, aimed at restoring the site to

its

pre-historic appearance, gives this theory further substance. Many have likened

it to a grounded

flying saucer

; and it is the subject of much controversy.

However, during the Newgrange

excavations between 1962 - 1965, much research focused on the original shape of

the cairn. This information was drawn from the accounts

of those who had

visited the monument in the preceding

centuries

: all of them commented on its flat top. And the positioning of the white

quartz stones that reinforce

the front of the mound is based entirely on

meticulous engineering analysis of the cairn collapse.

As with Newgrange, which can still be seen with the naked eye from the Hill of

Tara, some 15 miles (10 kilometres) away, they tend to be situated

on hill tops

and commanding sites. The mound is enclosed on the outside by a

circle of standing stones

of which twelve remain. This gives the impression that the

monument

was built

and designed to stand out from the landscape - perhaps as a beacon for pagan

worship. The present day reconstruction, aimed at restoring the site to

its

pre-historic appearance, gives this theory further substance. Many have likened

it to a grounded

flying saucer

; and it is the subject of much controversy.

However, during the Newgrange

excavations between 1962 - 1965, much research focused on the original shape of

the cairn. This information was drawn from the accounts

of those who had

visited the monument in the preceding

centuries

: all of them commented on its flat top. And the positioning of the white

quartz stones that reinforce

the front of the mound is based entirely on

meticulous engineering analysis of the cairn collapse.

The white quartz gives the monument a particularly startling facade, and it is

worth noting that this was only positioned at the front of the cairn, facing

the sun.

White quartz is known for its energy-dispersing properties and it may,

therefore, have been used to absorb and channel its

life-giving energy

, or it may simply have

provided further visibility to those wishing to reach

the site. In addition, there were large numbers of oval granite boulders found

amongst the collapsed quartz facade.

These have been scattered randomly through

the reconstructed facade, without

acknowledgement to any possible use for these

dark stones as patterning elements within

the quartz.

The white quartz gives the monument a particularly startling facade, and it is

worth noting that this was only positioned at the front of the cairn, facing

the sun.

White quartz is known for its energy-dispersing properties and it may,

therefore, have been used to absorb and channel its

life-giving energy

, or it may simply have

provided further visibility to those wishing to reach

the site. In addition, there were large numbers of oval granite boulders found

amongst the collapsed quartz facade.

These have been scattered randomly through

the reconstructed facade, without

acknowledgement to any possible use for these

dark stones as patterning elements within

the quartz.

The twentieth century

restorers

were not prepared to risk a spiral pattern. The reasons for the use of quartz

and granite, and their design, must have been

of

consequence because the

builders of the Newgrange went to great lengths to put the stones there. They

are not found locally. The nearest place that they could have collected

the

quartz was from the Wicklow Mountains to the South; and such a

journey

would have taken them seven days going by canoe along the Boyne and down the

coast.

The granite was probably collected around the

Mourne Mountains

, some days away to the North.

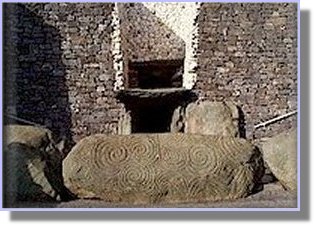

The cairn itself is reinforced at its base by a continuous circle of stones,

called kerb stones. Many of these are ornamented. The most spectacular of these

are the entrance stone,

and the stone opposite the entrance on the other side

of the mound. There is much speculation as to the meaning of these complex

designs, and many consider them to have solar

symbolism as

sun worship

was the most widely spread cult in pre-historic Europe.

One of the most interesting features of the mound, particularly in view of the

fact

that it is

a

feature unique to Newgrange, is the roof-box above the

entrance to the passageway.

It consists of two low side-walls, a back corbel

and a roofstone, and it is through this gap

that the dawn sun beams on the

morning of the

winter solstice. Its true purpose is

unknown, but some speculate that the

builders

must have held the sun in such reverence

that they gave it a separate

entrance to the giant tomb.

Entering the passage tomb is a remarkable

experience: the corbelled roof extends to 19 feet, or

almost 6 metres, in height, and the central chamber

has three recesses

which contain massive stone

basins that are thought to have been receptacles for

cremated remains, but they may also have had

other ceremonial functions. Many of the orthostats

or standing stones lining the passage-way are

decorated. The eastern recess shows the most

decoration and once again this points to

sunworshipping,

since the

sun rises in the east. The

pre-Celtic inhabitants had no

written language.

This

has lead to the thinking that the artwork at

Newgrange, comprised mainly of

three-dimensional geometric designs, must have

described the world in which they lived. Their complex patterns of loops,

spirals, diamonds, zig zags and lozenges reveals a concern

for harmony and

balance of pattern, rather than with anthropological / representational art;

and in this sense, it seems quite spiritual in nature. Some interpretations of

the symbols

give substance to the argument that its builders were probably

sunworshippers. The suggestion that

Aonghus

was a sun deity lends further support to this interpretation.

The cairn itself is reinforced at its base by a continuous circle of stones,

called kerb stones. Many of these are ornamented. The most spectacular of these

are the entrance stone,

and the stone opposite the entrance on the other side

of the mound. There is much speculation as to the meaning of these complex

designs, and many consider them to have solar

symbolism as

sun worship

was the most widely spread cult in pre-historic Europe.

One of the most interesting features of the mound, particularly in view of the

fact

that it is

a

feature unique to Newgrange, is the roof-box above the

entrance to the passageway.

It consists of two low side-walls, a back corbel

and a roofstone, and it is through this gap

that the dawn sun beams on the

morning of the

winter solstice. Its true purpose is

unknown, but some speculate that the

builders

must have held the sun in such reverence

that they gave it a separate

entrance to the giant tomb.

Entering the passage tomb is a remarkable

experience: the corbelled roof extends to 19 feet, or

almost 6 metres, in height, and the central chamber

has three recesses

which contain massive stone

basins that are thought to have been receptacles for

cremated remains, but they may also have had

other ceremonial functions. Many of the orthostats

or standing stones lining the passage-way are

decorated. The eastern recess shows the most

decoration and once again this points to

sunworshipping,

since the

sun rises in the east. The

pre-Celtic inhabitants had no

written language.

This

has lead to the thinking that the artwork at

Newgrange, comprised mainly of

three-dimensional geometric designs, must have

described the world in which they lived. Their complex patterns of loops,

spirals, diamonds, zig zags and lozenges reveals a concern

for harmony and

balance of pattern, rather than with anthropological / representational art;

and in this sense, it seems quite spiritual in nature. Some interpretations of

the symbols

give substance to the argument that its builders were probably

sunworshippers. The suggestion that

Aonghus

was a sun deity lends further support to this interpretation.

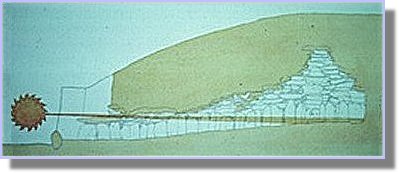

At dawn on the morning of the Winter Solstice every year, just after 9am, the sun begins to rise across the Boyne Valley from Newgrange over the ridge of a

hill known locally as Red Mountain. Given the right weather conditions, the

event is spectacular. At precisely four and a half minutes past nine, the light from the rising sun

strikes the front of the huge mound, and enters the passageway through the roofbox

which was specially designed to capture the rays of the sun. For the following fourteen minutes, the beam of light stretches into the passageway and on into the central chamber, where, in Neolithic

times, it illuminated the rear stone of the central recess of the chamber. Although the passageway apears level as one enters the tomb, it actually slopes upwards, in order that the rays of the rising sun may strike the back of the chamber at exactly the right point.

Through simple technology based on the alignment of stones, the people who constructed the tomb in those ancient days captured a very significant astronomical and calendrical moment in the most spectacular way possible. At dawn on the morning of the Winter Solstice every year, just after 9am, the sun begins to rise across the Boyne Valley from Newgrange over the ridge of a

hill known locally as Red Mountain. Given the right weather conditions, the

event is spectacular. At precisely four and a half minutes past nine, the light from the rising sun

strikes the front of the huge mound, and enters the passageway through the roofbox

which was specially designed to capture the rays of the sun. For the following fourteen minutes, the beam of light stretches into the passageway and on into the central chamber, where, in Neolithic

times, it illuminated the rear stone of the central recess of the chamber. Although the passageway apears level as one enters the tomb, it actually slopes upwards, in order that the rays of the rising sun may strike the back of the chamber at exactly the right point.

Through simple technology based on the alignment of stones, the people who constructed the tomb in those ancient days captured a very significant astronomical and calendrical moment in the most spectacular way possible.

Today Newgrange stands unique as a cathedral of the megalithic age, a monument to a long-vanished race known only through myth and legend as the Tuatha Dé Danaan, the semi-divine ancestors of the Gaels.These later Celtic invaders of Ireland worshipped the Tuatha Dé Danaan as gods, and made Newgrange the centre of their cult of the dead, designating it as the dwelling place of the Dagda and his son

Aonghus. This ancient belief survives to the present time. Today Newgrange stands unique as a cathedral of the megalithic age, a monument to a long-vanished race known only through myth and legend as the Tuatha Dé Danaan, the semi-divine ancestors of the Gaels.These later Celtic invaders of Ireland worshipped the Tuatha Dé Danaan as gods, and made Newgrange the centre of their cult of the dead, designating it as the dwelling place of the Dagda and his son

Aonghus. This ancient belief survives to the present time.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()